In the last decade, “microservices” architectures have come into fashion for a variety of reasons.

Like “Agile”, this term has taken on many meanings and interpretations over the years and — in many cases — has come to represent even not-so-micro-services. Whether true microservices like single-purpose serverless functions or “macroservices” where logical parts of the system are broken out into different codebases deployed as separate services connected by remote API calls, I have never been a fan of such architectures because of the inherent complexities and unnecessary developer experience friction that accompanies such design choices.

It is not to say that there are no use cases for such architectures (see the addendum), but that the paradigm itself is often inappropriately overused and adds cost to every action, hindering teams more than helping.

This is especially true for startups where microservices can add too much complexity too early — whether it’s development complexity, deployment complexity, or operational complexity — but holds just as true for enterprise teams seeking to move fast.

In more recent years, there has been a backlash against this movement.

In his essay Complexity is killing software developers, Scott Carey writes:

The shift from building applications in a monolithic architecture hosted on a server you could go and touch, to breaking them down into multiple microservices, packaged up into containers, orchestrated with Kubernetes, and hosted in a distributed cloud environment, marks a clear jump in the level of complexity of our software.

“There is a clear increase in complexity when you move to such a pervasive microservices environment,” said Amazon CTO Werner Vogels during the AWS Summit in 2019. “Was it easier in the days when everything was in a monolith? Yes, for some parts definitely.”

Carey makes the case that such complexity is “accidental” as opposed to “necessary” to the domain and as such can sap the focus of the team from solving the core business problems.

Jason Warner, former CTO of GitHub, wrote in tweet in 2022:

Jason Warner

Jason Warner

@jasoncwarner

I'm convinced that one of the biggest architectural mistakes of the past decade was going full microservice

On a spectrum of monolith to microservices, I suggest the following:

Monolith > apps > services > microservices

So, some thoughts

8:45 PM · Nov 14, 2022

I’m convinced that one of the biggest architectural mistakes of the past decade was going full microservice

On a spectrum of monolith to microservices, I suggest the following:

Monolith > apps > services > microservices

Last year, a team from Google published a new paper titled Towards Modern Development of Cloud Applications that throws more fuel on the (dumpster) fire of microservices architectures:

When writing a distributed application, conventional wisdom says to split your application into separate services that can be rolled out independently. This approach is well-intentioned, but a microservices-based architecture like this often backfires, introducing challenges that counteract the benefits the architecture tries to achieve. Fundamentally, this is because microservices conflate logical boundaries (how code is written) with physical boundaries (how code is deployed).

Indeed, this is a very fundamental flaw in thinking with respect to microservices and their place in systems architecture.

The authors of the Google paper offer 5 reasons why such thinking can end up hindering teams:

It hurts performance. The overhead of serializing data and sending it across the network is increasingly becoming a bottleneck

It hurts correctness. It is extremely challenging to reason about the interactions between every deployed version of every microservice.

It is hard to manage. Rather than having a single binary to build, test, and deploy, developers have to manage 𝑛 different binaries, each on their own release schedule.

It freezes APIs. Once a microservice establishes an API, it becomes hard to change without breaking the other services that consume the API.

It slows down application development. When making changes that affect multiple microservices, developers cannot implement and deploy the changes atomically.

These reasons are particularly important to consider in the context of a startup as the small team sizes and importance of speed of iteration and deployment negate many of the reasons why a microservices approach might be better (for example, team boundaries that define procedural boundaries).

For startups and enterprise teams alike, understanding how to build “modular monoliths” (“MoMo”) can help increase velocity and reduce the drag caused by the friction of microservices.

Our objective isn’t to recreate the Google paper’s architecture, but to meet the same goals of increasing velocity with a monolithic codebase that still affords flexibility in deployment. Let’s explore how with a practical example in .NET.

• • •

A Practical Guide in .NET

In the paper, the authors propose a solution paradigm:

The two main parts of our proposal are (1) a programming model with abstractions that allow developers to write single-binary modular applications focused solely on business logic, and (2) a runtime for building, deploying, and optimizing these applications.

While the proposed solution design in the paper introduces appropriate complexity for Google’s concerns, it is possible to imagine a simpler version of this paradigm that can be scaled and adapted accordingly in complexity as needed.

.NET feels particularly suited for this because of its generic host model. In short, whether the goal is to run a REST API or a console app, in .NET, it can be run as the service workload of a “host”.

In this model, the responsibility of the host is to simply configure the runtime by loading the required services and configuration and then executing those services. In other words, it precisely separates the application and business logic from the runtime and how the application is deployed.

To see the full code example, follow along here: A Practical Guide to Modular Monoliths (MoMo) with .NET

Our Sample Domain

In this example, the domain is a simple project management application with only 3 entities:

- Project. Our tasks or WorkItems are associated with a Project.

- WorkItem. Each WorkItem is linked to a single Project and has one or more User collaborators.

- User. A simple entity representing the assignees of the WorkItems.

💡 I didn’t use the nomenclature Task as this is a system type name.

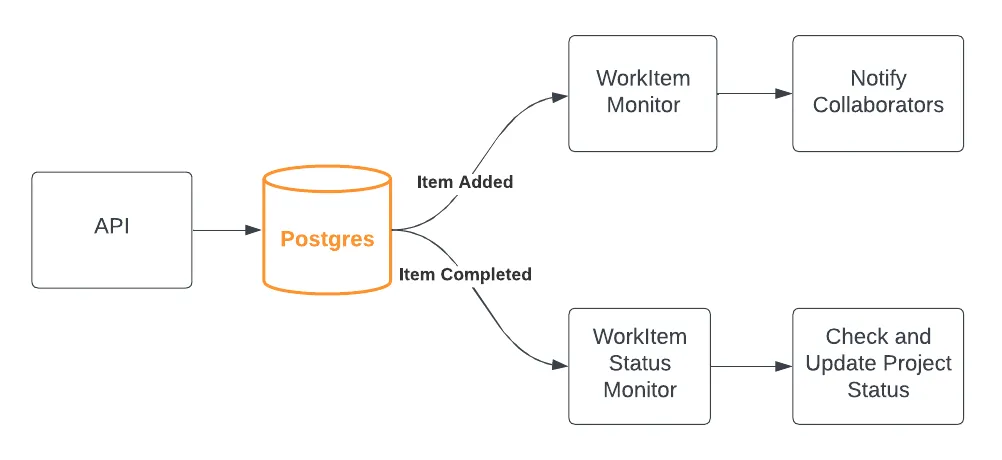

The system is responsible for doing two things when a WorkItem has its status set to Completed:

- Send a notification to each of the User collaborators.

- Check to see if all of the WorkItems for the Project are completed and, if so, mark the Project as completed.

With a microservices architecture, each of these responsibilities would be developed and deployed as separate pieces of code potentially sharing only a service or message contract.

In this modular monolith, decoupling these two actions from the main action of updating the the status of the task remains a goal. However, by choosing to contain the core logic in a single binary that can be parceled at the runtime level, it affords several luxuries as described by the authors of the Google paper such as better local DX.

This example is kept quite basic by integrating at the database layer, but it is not hard to imagine how this could also be done with messaging instead through SQS or Google Cloud Pub/Sub.

Separating Service from Runtime

In total, the system will have 3 components:

- The API that contains all of the logic to mutate the state of the system from external callers.

- The WorkItemMonitorService which will periodically check for new WorkItems.

- The WorkItemStatusMonitorService which will periodically check for the status of WorkItems for a given Project.

The logical structure of our application with an API that updates a Postgres database. Two services are responsible for watching for changes and performing additional actions out-of-band. In this simple case, we use the database as signaling layer, but it is easy to swap this out for an event queue like SQS.

A key to making this work is to separate the logic of the service from the runtime container for the service. This is quite straightforward and natural with .NET’s host paradigm because of the built-in dependency injection framework that allows selection and configuration of the services to load into the host at runtime.

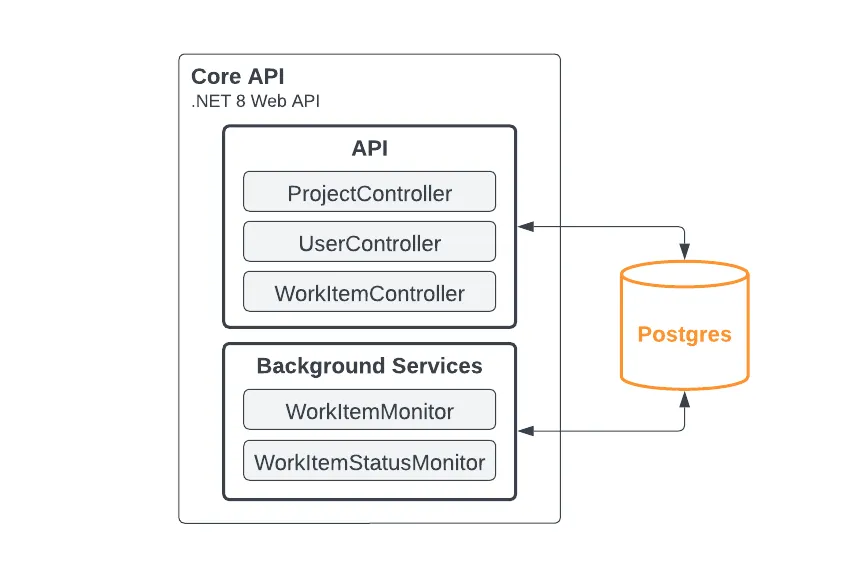

In this example, all of the application logic is implemented in the core project and during development on the local machine environment, the single API host runtime will load all of the components into one runtime including our two services:

// The core API runtime, SetupServicesExtension.cs

// True when ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT or DOTNET_ENVIRONMENT is "Development"

if (RuntimeEnv.IsDevelopment) {

services.AddHostedService<WorkItemMonitorService>();

services.AddHostedService<WorkItemStatusMonitorService>();

}

The local development runtime components; everything in a single process for ease of startup, tracing, debugging, and development.

For development, this simplicity makes it easier when debugging, testing locally, and especially when onboarding new engineers. A single command brings up the entire runtime with all of the services running in one process — making it easy to develop, test, and debug locally:

cd src/core

dotnet run # One command to start everything in one process

When running this in production, neither of the monitoring services are loaded into the API runtime which makes the API runtime suitable for scale-to-zero serverless container runtimes like Google Cloud Run or Azure Container Apps. If there is no need to scale-to-zero, an option is to flag which services to add and simply have one single container image that can run different “slices” of our codebase by loading different services based on environment variables.

In fact, this is how the second service runtime will be configured.

To start with, modify the svc.csproj to automatically copy the configuration files over on build to reduce mistakes from manually copying and synchronizing configuration:

<!--

Copies the runtime configuration

-->

<Target Name="CopyRuntimeConfig" AfterTargets="Build">

<Message Text="Copying runtime config..." Importance="high" />

<Exec Command="cp ../core/appsettings*.json ." />

</Target>

The responsibility of the host runtime is only to set up the dependency injection container and load the relevant services:

builder.Services.Configure<MoMoConfig>(

builder.Configuration.GetSection(nameof(MoMoConfig))

);

var role = Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("SVC_ROLE");

if (role == nameof(WorkItemMonitorService))

{

// Run single service

Console.WriteLine("Loading WorkItemMonitorService service");

builder.Services.AddHostedService<WorkItemMonitorService>();

}

else if (role == nameof(WorkItemStatusMonitorService))

{

// Run single service

Console.WriteLine("Loading WorkItemStatusMonitorService service");

builder.Services.AddHostedService<WorkItemStatusMonitorService>();

}

else

{

// Run both services

Console.WriteLine("Loading both services");

builder.Services.AddHostedService<WorkItemMonitorService>();

builder.Services.AddHostedService<WorkItemStatusMonitorService>();

}

builder.Services.AddDataStore();

var host = builder.Build();

host.Run();

When poring over the code, it is evident that it is a very thin wrapper around our core monolith. This wrapper, with its own host configuration, provides separation of the API endpoints from the services and simplifies the configuration at startup.

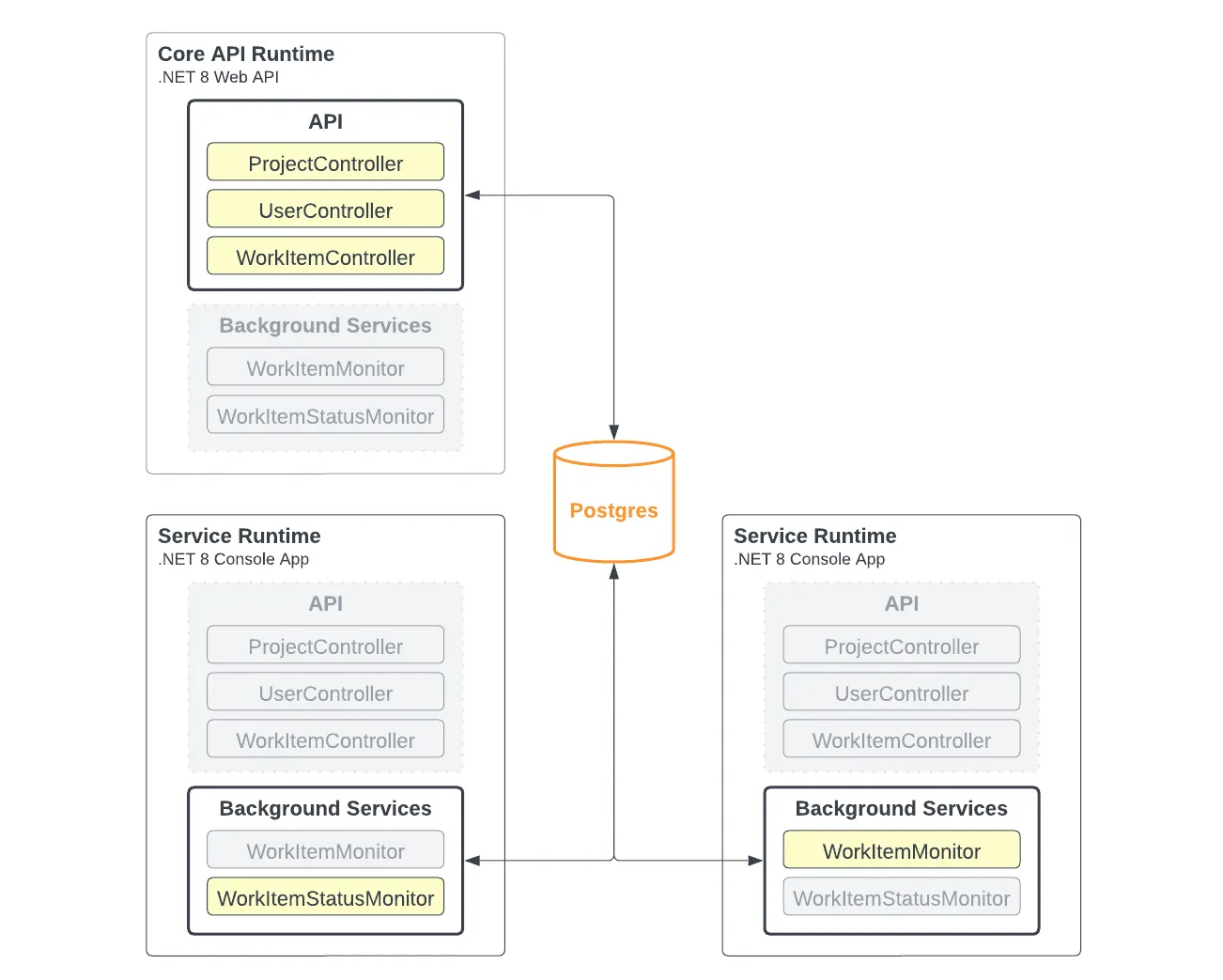

For example, if there is a need to run each in a separate runtime, we can easily do so by deploying 3 containers with different configurations:

While keeping one codebase, we can separate the responsibilities at runtime if we have a need to do so such as scaling the capacity of each of these services separately from the other.

The Docker Compose file docker-compose-run.yaml shows how this would look:

# The API in one container

api:

image: momo/api

build:

context: ./

dockerfile: ./Dockerfile.core

expose:

- 8080

ports:

- "8080:8080"

depends_on:

- postgres

networks:

- momo

# We run the work item status monitor

svc1:

image: momo/svc1

build:

context: ./

dockerfile: ./Dockerfile.svc

environment:

- SVC_ROLE=WorkItemStatusMonitorService

depends_on:

- api

networks:

- momo

# We run the new work item monitor

svc2:

image: momo/svc2

build:

context: ./

dockerfile: ./Dockerfile.svc

environment:

- SVC_ROLE=WorkItemMonitorService

depends_on:

- api

networks:

- momo

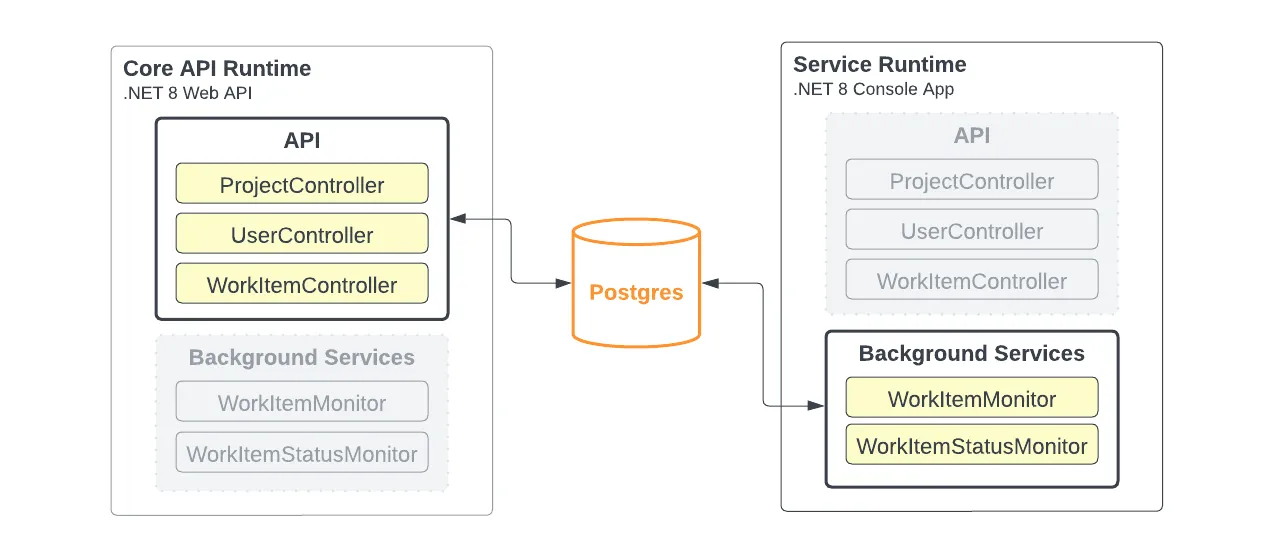

Alternatively, it’s also possible to configure our runtimes like this:

Only two separate runtimes with the API and background services separated.

Deployed as containers to Google Cloud Run, Azure Container Apps, or AWS ECS Fargate, it is possible to have one codebase and configure the environment variable on the container at runtime (or move the environment variable into the .Dockerfile and create multiple files instead). This is very efficient from a build perspective as there is only a need to build the one image despite having two distinct services because of the monolithic codebase.

This approach yields several positive outcomes just as described in the paper:

- The local DX is excellent: a single runtime to start, trace, and debug; there is no need to run multiple processes and perform complex tracing of inter-process data flows for local development.

- Packaging and deployment is straight forward and all dependencies ship at once. The .Dockerfile shows just how straight forward it is to ship this. In CI/CD, there's no need to set up complex build pipelines to build dependent projects and generate new bindings.

- It is still possible to deploy this application into a variety of topologies depending on how we need it to scale. For example, a load balancer sitting in front of two API only instances and a single instance running both services. If there is a need to scale the two services independently, it is possible to change the environment variable on the runtime and split two instances out.

• • •

Closing Thoughts

As the Google paper mentions, it is important to understand that how code is written (as a monolith) and how it is deployed (as separate services) are two separate concerns and understanding this difference can guide teams towards an architecture that is more sensible for the needs of the team.

It is not that microservices never make sense but that this style of application architecture can introduce so-called “accidental complexity” which can be crippling for small teams trying to move fast by creating more friction in every aspect of owning an application.

In the past decade, many teams defaulted to this style of architecture starting from a negative association of “monolith” with “legacy” or a misconception that separate microservices is the only way isolate responsibilities rather than considering that monolithic codebases can still allow teams to build modularly and isolate responsibility in services that are simply deployed into different runtime hosts.

Teams that find themselves struggling with the friction of working with microservices in their everyday workflow should consider whether moving to a modular monolith can help erase much of that friction yet still retain many of the benefits such as runtime isolation of responsibilities and independent scalability of services.

• • •

Addendum

So when do separate (micro)services make sense? Generally, I think there are a very small number of use cases for most teams:

- Team and process boundary isolation. If different teams have different release processes, it may make sense to isolate these processes at a service boundary.

- Deployment efficiency. For example, the base Playwright Docker image is quite hefty and it may be more efficient to deploy any code that is programmatically using Playwright separately from the main codebase.

- Platform fit. In some cases, tooling may make the choice of one language and platform over another more attractive. This is often the case with AI and ML where Python provides better tooling but the rest of the application stack may be in Java, Go, or .NET.

- Special cases. AWS CloudFront Functions and AWS Lambda @ Edge are both examples where moving very specific workloads close to the edge has benefits. For a use case like CloudFront Functions, the runtime limitations necessitate very targeted almost nano services.